MCP Servers, Ports, and Sharing: A Guide to Not Tripping Over Your Own Feet - Part 1 of 5

Part 1 of 6: The AI-Assisted Development Workflow Series

This is the first installment in a five-part series exploring how AI is transforming modern development workflows. In this series, I’ll walk through my journey of using an AI-assisted development environment effectively, from basic infrastructure setup to advanced architectural enforcement and task orchestration.

Series Overview:

- Part 1: MCP Servers, Ports, and Sharing - Setting up the foundation

- Part 2: ESLint Configuration Refactoring - Cleaning up tooling with AI

- Part 3: Custom Architectural Rules - Teaching AI to enforce design patterns

- Part 4: Task Orchestration - Managing complex refactoring workflows

- Part 5: Project Rules for AI - Creating effective memory banks and guidelines

- Part 6: The Ultimate Design Review - Putting it all together

I’ve been spending a lot of time lately in the world of AI agents… wait, no, that’s not it. The Model Context Protocol. MCP. It’s a fancy way of saying “a way for AI models to talk to tools,” and it’s pretty powerful. But like any new toy, it comes with its own set of “some assembly required” headaches. Today, I want to talk about one of those: managing MCP servers, avoiding port conflicts, and generally keeping your digital workspace from turning into a tangled mess of wires.

What in the World is an MCP Server?

Think of an MCP server as a translator. Your AI model speaks “I want to do something,” and the MCP server translates that into “Okay, computer, run this specific command.” It’s a bridge between the high-level thinking of the AI and the low-level reality of your machine.

You need to know about them because, suddenly, you’re not just running a single AI model; you’re running a whole suite of tiny little helper applications. Each one of these helpers, or “tools,” might need its own MCP server. Want to browse the web? That’s a server. Want to read and write files? That’s another server. Before you know it, you’ve got a whole digital office full of very specialized, very chatty interns.

So, when do you start one? The simple answer is: when you want to use a tool. The more complicated answer is: when you want to use a tool that needs a dedicated process to listen for instructions.

Nomenclature

Before we dive deeper, let’s clarify some terminology that might seem counterintuitive at first. In the MCP ecosystem, what we call an “MCP server” is actually a client from the perspective of your editor or CLI tool.

Here’s the mental model: Your editor (like VS Code, Cursor, Windsurf) or CLI tool is the “server” that coordinates everything. It’s the central hub that manages the conversation with the AI model and decides which tools to invoke. The MCP servers are specialized “clients” that connect to this central hub to provide specific capabilities.

Think of it like a restaurant: Your editor is the head chef who takes orders and coordinates the kitchen. The MCP servers are like specialized sous chefs - each one is an expert at a particular type of cooking (browsing the web, reading files, querying databases, etc.). The head chef doesn’t know how to do everything, but they know which sous chef to call for each specific task.

So when we say “MCP server,” we’re really talking about a specialized client that serves a particular function to the main AI coordination system. This naming convention can be confusing, but it’s become standard in the MCP community.

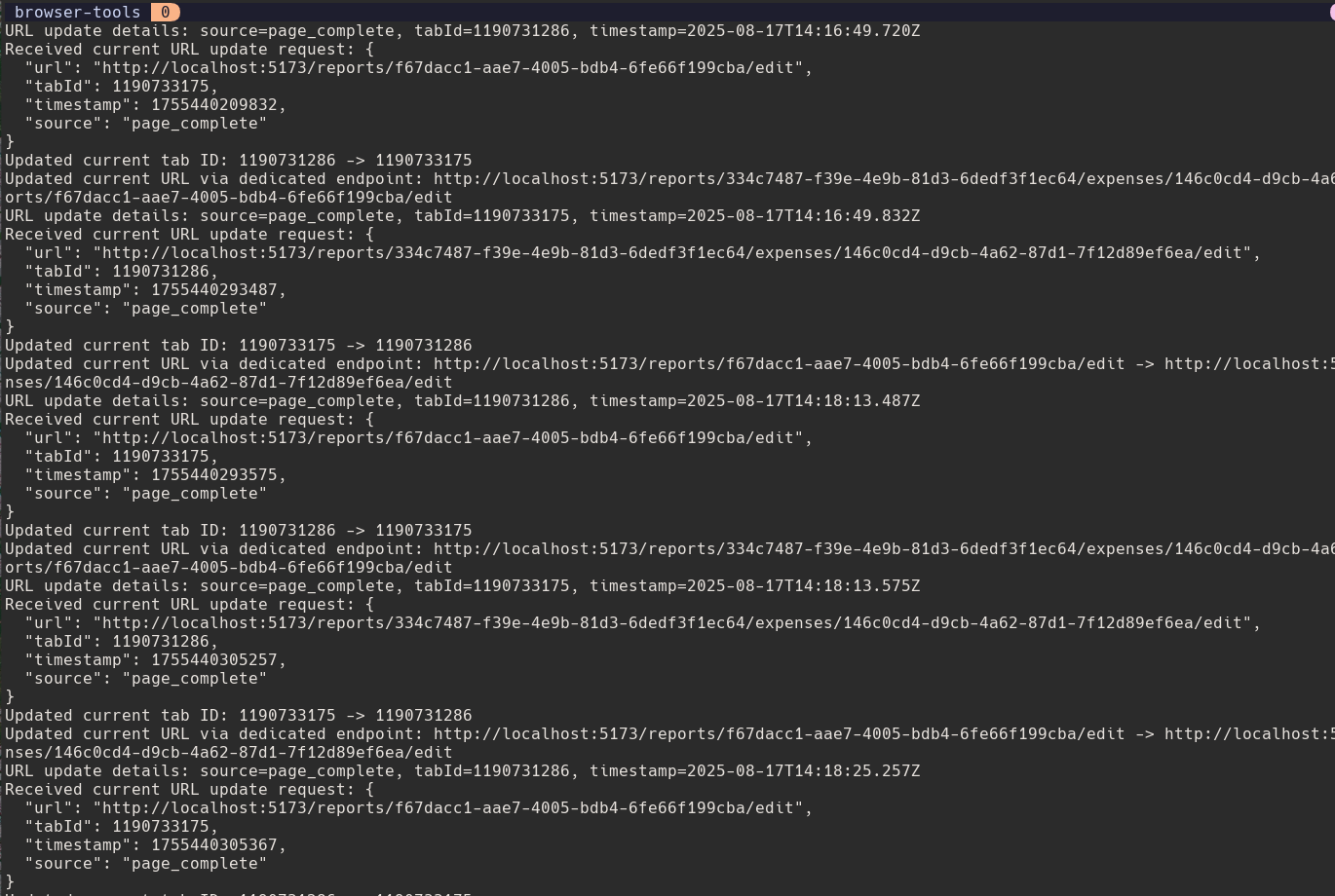

Where this can get really confusing is if the tool you are wanting to use also requires communicating with a server. I really like BrowserTools MCP. This tool exposes your console logs to your browser, giving it access to your frontend development logs as you make changes. It’s a complex tool, though, which requires:

| Component | What It Is | Installation Method | Purpose |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chrome Extension | Browser extension that captures console logs and network requests | Download from GitHub and load as unpacked extension | Captures browser activity and sends it to the server |

| MCP Server | Model Context Protocol server that exposes tools to your AI editor | |

Provides AI with access to browser tools and logs |

| BrowserTools Server | Node.js server that aggregates logs and handles screenshots | npx @agentdeskai/browser-tools-server@1.2.0 |

Runs on port 3025, manages websockets and log aggregation |

So when you say “BrowserTools MCP,” you’re actually talking about three separate components working together - the browser extension, the MCP server, and the BrowserTools server. This is a perfect example of why port management becomes crucial in AI-assisted development.

Types of MCP Servers

MCP servers come in two main flavors, and understanding the difference is crucial for managing your development environment effectively.

stdio-based Servers

These are the simplest type of MCP server. They communicate through standard input/output streams, which means they’re designed to be short-lived processes that start when needed and exit when the work is done. Think of them like command-line tools that your AI can invoke.

Characteristics:

- No port management needed - They don’t bind to any network ports

- Stateless by design - Each invocation is independent

- Perfect for one-off tasks - File operations, code generation, data processing

- Easy to debug - You can run them directly from the command line

Example use cases:

- File system operations (reading, writing, searching files)

- Code formatting and linting

- Data transformation and analysis

- Simple API calls and data fetching

Port-based Servers

These are the more complex beasts that we’ll focus on in this post. They run as persistent HTTP servers that bind to specific ports on your machine.

Characteristics:

- Persistent processes - They stay running and maintain state

- Port binding required - Each server needs its own port

- Stateful operations - Can maintain context across multiple requests

- Network communication - Use HTTP/WebSocket protocols

- Resource intensive - They consume memory and CPU while running

Example use cases:

- Database connections and queries

- Web browsing and page interaction

- Complex tool integrations (like GitHub, Slack, etc.)

- Real-time data streams and monitoring

Why This Matters for Your Workflow

The distinction becomes important when you’re building an AI-assisted development environment. stdio-based servers are great for simple, stateless operations, but you need to understand which type of server you are utilizing.

I tend to have multiple windows open of Cursor, or might be running Cursor and gemini in a terminal shell. What if I want to share an MCP server (like we will discuss in part 4) across my different windows/sessions?

This is where the port management challenges come in. To make it even more complicated, you might have several port-based servers running simultaneously:

- A browser automation server on port 3000

- A database connection server on port 3001

- A file system watcher on port 3002

- A custom tool integration on port 3003

Managing these ports, ensuring they don’t conflict, and keeping track of which server is doing what becomes a real challenge. That’s exactly the problem we’ll solve with our tmux-based orchestration system.

The Port Authority is Now in Session

Many of these MCP servers use HTTP to communicate. That means they need to “bind” to a specific port on your computer. A port is like a numbered door on your computer. Only one application can be listening at a specific door at a time. If you try to start two servers on the same port, the second one will crash and burn, complaining about the port being “already in use.”

This is a classic problem in software development, and it’s now a problem for those of us building with AI. But here’s the cool part: if an MCP server is just a simple HTTP server, you can often share it between different AI models. As long as they’re all speaking the same language (i.e., the same MCP specification), they can all talk to the same server on the same port. No need to spin up a new server for each model.

My Not-So-Secret Weapon: tmux and servers.mcp

As I started collecting more and more of these MCP servers, I realized I needed a better way to manage them. I’m a big fan of tmux, a terminal multiplexer that lets you have multiple terminal sessions running in the same window. It’s like having a whole bunch of little command-line windows open at once, but without the clutter.

So, I came up with a little convention for myself. I created a file called servers.mcp that lists all the servers I want to run. It’s a simple text file, with each line containing a name for the server and the command to start it, separated by an equals sign.

Here’s what my servers.mcp file looks like:

browser-tools=npx -y @agentdeskai/browser-tools-server@latest

mpc-tasks=TRANSPORT=http PORT=4680 npx mcp-tasksThen, I wrote a little shell script called start-mcp-servers.sh that reads this file and starts up a new tmux session with a separate window for each server.

Here’s the script:

#!/bin/bash

# MCP Server Launcher Script

# Reads servers.mcp and creates tmux windows for each server

# Colors for output

RED='\033[0;31m'

GREEN='\033[0;32m'

YELLOW='\033[1;33m'

BLUE='\033[0;34m'

NC='\033[0m' # No Color

# Check if tmux is installed

if ! command -v tmux &>/dev/null; then

echo -e "${RED}Error: tmux is not installed${NC}"

echo "Please install tmux first:"

echo " Ubuntu/Debian: sudo apt install tmux"

echo " macOS: brew install tmux"

echo " Arch: sudo pacman -S tmux"

exit 1

fi

# Change to the script's directory

cd "$(dirname "$0")"

# Check if servers.mcp exists

if [ ! -f "servers.mcp" ]; then

echo -e "${RED}Error: servers.mcp file not found${NC}"

exit 1

fi

# Check if tmux session already exists

if tmux has-session -t mcp-servers 2>/dev/null; then

echo -e "${YELLOW}MCP servers session already exists. Attaching...${NC}"

tmux attach-session -t mcp-servers

exit 0

fi

# Function to clean up tmux session if script is interrupted

cleanup() {

echo -e "\n${YELLOW}Cleaning up...${NC}"

tmux kill-session -t mcp-servers 2>/dev/null

exit 1

}

# Set up signal handlers

trap cleanup SIGINT SIGTERM

echo -e "${BLUE}Starting MCP servers in tmux session...${NC}"

# Create new tmux session

tmux new-session -d -s mcp-servers -n "mcp-servers"

# Read servers.mcp file and create windows

window_count=0

while IFS='=' read -r title command;

do

# Skip empty lines and comments

if [[ -z "$title" || "$title" =~ ^[[:space:]]*# ]]; then

continue

fi

# Trim whitespace

title=$(echo "$title" | xargs)

command=$(echo "$command" | xargs)

if [ -n "$title" ] && [ -n "$command" ]; then

echo -e "${GREEN}Creating window: $title${NC}"

echo -e " Command: $command"

if [ $window_count -eq 0 ]; then

# First window - rename the default window

tmux rename-window -t mcp-servers:0 "$title"

tmux send-keys -t mcp-servers:0 "$command &" C-m

else

# Create new window

tmux new-window -t mcp-servers -n "$title" "$command"

fi

window_count=$((window_count + 1))

fi

done <servers.mcp

if [ $window_count -eq 0 ]; then

echo -e "${RED}No valid servers found in servers.mcp${NC}"

tmux kill-session -t mcp-servers 2>/dev/null

exit 1

fi

echo -e "${GREEN}Created $window_count MCP server windows${NC}"

echo -e "${BLUE}Attaching to tmux session...${NC}"

echo -e "${YELLOW}Use Ctrl+B then D to detach from the session${NC}"

echo -e "${YELLOW}Use 'tmux attach -t mcp-servers' to reattach later${NC}"

# Attach to the session

tmux attach-session -t mcp-serversNow, when I want to start up my MCP environment, I just run ./start-mcp-servers.sh, and I get a nice, clean tmux session with all my servers running in their own windows.

Here’s what it looks like:

This setup makes it easy to see what’s going on with each server, and I can easily restart a server if it crashes. It’s a simple solution, but it’s made my life a lot easier. And, most importantly, it keeps me from tripping over my own digital feet.

m tripping over my own digital feet.